Cause and Affect

With every terrible event, my mind can’t stop from focusing on its contingency: it didn’t have to be this way. It almost wasn’t. If we knew better, we could prepare.

This is a personal reflection going back over some of the ideas and feelings I have previously written about.

Once again I’m lost in timelines. People make predictions—not singular ones, an array of possibilities extrapolating from current events, political platforms, and historical precedents. I listen and think, how extraordinary the way these minds work; I have no mind for such strategic thinking. My mind is stuck on the alternate presents and futures from past timelines, wishing it wasn’t so, imagining the myriad other possibilities that felt tangible in those moments, or perhaps even more real now when they are out of my grasp. This is a form of grief, but a strange one as it relates to things that were never there. Freud said we can mourn ideals and nations, how about imaginary futures?

He also said we can mourn nations. For an anti-statist, what a strange predicament to imagine. And yet, faced with the possible destruction of the structures that have shaped and enabled my life for what it is (while also disabling it, enabling it at a certain point of tension, better off than others, but still vulnerable in many ways) . . . do I mourn the old world, the world whose destruction I wish for? My refusal to imagine a future, to invest in a dream, is not just a principle that we are only able to imagine futures that in some way replicate the current structures. It is also perhaps a combination of fear, inability, and will. Bartleby’s “I prefer not to.”

None of the possibilities I’ve listened to friends and comrades unravel are “good.” The conditions have never been conducive, can never meet the utopian expectations of the stateless societies we spin into the world whole cloth. Most of our utopias don’t tell the story of how we got there. Octavia Butler’s parable books, instead, shows how the utopian vision is birthed in violence and a form of authoritarianism. The utopia, no matter how non-hierarchical, becomes a Procrustean bed, where you cut off the legs to fit the frame.

So my realistic friends adept at realpolitik spin out the complicated pathways of violence, struggle, and possibility—what any revolutionary movement has always faced. There is still the undercurrent that we could win . . . if. And then what we live through is not like the apocalypse or dystopia that pop culture incessantly rams down our throats. It’s much more normal. It’s out there, it’s looming—and for us in the imperial core, there is also a consistency to our days, good and bad. Bracing for the rise in price of bread, while supplies last, the push me pull you of insistent fascism and retreat in the face of pressure—the state of confusion is actually the power that leaves us most vulnerable. That and our comfort, whatever that is.

With every terrible event, my mind can’t stop from focusing on its contingency: it didn’t have to be this way. It almost wasn’t. If we knew better, we could prepare. We knew and didn’t do the right things. We carried the seed of destruction within us the whole time . . . It’s a neurosis, it’s an anxiety, can I learn from it? I don’t mean, can I fix myself, but can I find meaning in this tendency? In the present, I grip so hard, constantly hanging on the precipice by my fingertips, everything dire, everything almost failed. Fantastic self-soothing, this grasp at the past and its alternate future. Maybe. A reminder that nothing is inevitable (sitting in the doom of inevitability). An obsessive attempt at control over things beyond me.

One of the reasons I believe in these alternative timelines is that I think we live in a reverse Candide, the worst of all possible worlds—or the stupidest of all possible worlds. This attitude has been borne out most clearly by the Bond villain embodiment of Trump and his people. Sitting on a gold throne (toilet), decreeing Nazi-reeking policies of eugenics and genocide, purposefully destroying the economy out of dogged masculine naturalism (muscular Christianity) or some form of constipation like Martin Luther, antisemitically punishing antisemitism, a stream of piss so stinking it makes you search for any feasible cause—it’s so blatant that the New York Times’ normalization can’t even convince the liberals.

And nevertheless, she persists.

The leviathan moves its slow thighs in the onward crush of history that tramples all beneath. Indifferent history, no care for who lives and who dies, always over our shoulder, closer than it appears. My retroactive thinking—Nachträglichkeit—does its best to find a determinate history, it moves through dialectics, towards spirit, towards communism, towards total war. What are our dreams against the endless violence and destruction?

And yet, there are so many moments of beauty and joy, accessible even from within our cocoons of terror. If anarchism means anything practical in my life, it is in the discontinuous production of these moments of encounter where the world explodes in a good way: we are there, clearly defined, and the backdrop fits our contours. The flash of a camera, and then we move again. Life might be the boring in between times rarely represented in narratives, or life might be a handful of exquisite moments, life with the scent of death, the windrush while you drop.

“A counted number of pulses only is given to us of a variegated, dramatic life. How may we see in them all that is to be seen in them by the finest senses? How shall we pass most swiftly from point to point, and be present always at the focus where the greatest number of vital forces unite in their purest energy?”

And yet the times I feel most me are lying awake in bed, head spinning on everything lost, damning myself for my inability. Life is the most painful. But I don’t want to greedily hunger for these moments, think I can gather a handful and sate myself. Life needs its downtimes and downturns. Anarchism means nothing, it’s a name attached to what we want, what we do, what we tend towards. And every name misses its mark. We cannot be contained. History cannot contain us.

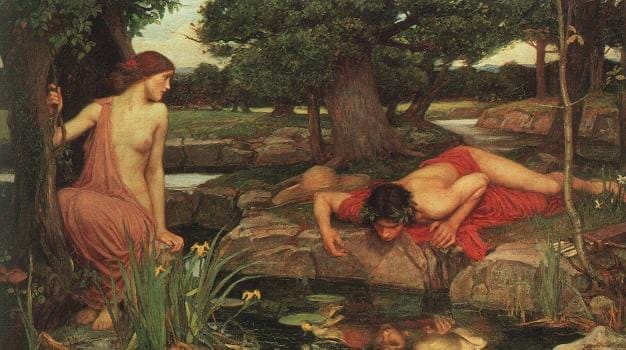

My haunted house is not just peopled with former friends and lovers, but all the things that could not be and never were. My ghosts are possibilities that haunt impossibilities. There are endless things to mourn. My spiritual hunger clamps down these dead futures to feed the fire of the past I can’t access but long to curl up in. The moment before. When all was possible. When the air was charged as before a storm.